When the world ends, you'll be glad you can build a radio (even if you can't remember how)

Why (and how) I Built a Radio with AI Coding Tools

I'm a Creative Technologist at Indeed, where I work within our in-house agency identifying tools that help creatives—graphic designers, copywriters, art directors, videographers—do their best work. My role is vital because there are so many creative AI tools available, and many startups haven’t built them with creatives in mind. The weakest creative tools are designed for those who ask for work, not for those who create it. That’s why I spend my days testing new tools, listening to my team discuss AI, and exploring ways to automate without losing sight of the craft.

I've also been writing code since I was eight years old, starting with Logo, a simple drawing application that taught me the fundamentals of programming. Those days typing out simple lines of code in my elementary school’s basement set me on a path that would become one of the greatest joys of my life. The act of coding demystified technology by turning boring beige boxes into powerful systems that could do almost anything as long as you spoke their language.

So, some 30 years later, sitting in front of a different screen in a different basement, I felt a pleasant ripple course through my brain upon reading the word "vibecoding" in a tweet by Andrej Karpathy. This half-joking term for building software through a novel mix of intuition and advanced coding agents would soon explode into a parade of vaporware, SaaS fails, and calls for the end of coding as a profession. Meanwhile, I saw in this moment a reflection of the demystification of technology that I experienced at the age of eight. AI-assisted coding could allow many more people to experience the joy of making computers do whatever they can manage to communicate clearly.

To test this theory, I needed a project. I thought it should be concrete and straightforward – no disruption or 10x-ing my investment. No social feeds. Around the same time, I was really into internet radio and listening to real stations online. And I was disappointed by the options currently available on the web. They were either terribly designed or riddled with ads (often both). There was also a quaint poetry to the idea of developing a radio app. For generations, building a radio has served as the gateway project for aspiring electrical engineers. Both radios and simple programs require working with widely available components to create something that behaves in predictable ways. Both provide clear success criteria. Most importantly, both offer that sense of self-sufficiency upon completion. When the world ends, you'll be glad you can build a radio, even if you can't remember exactly how all the components work together.

I started my radio project, Not My First Radio, using Cursor, but quickly hit limitations as the codebase grew and switched to Claude Code. What emerged was more sophisticated than I expected: a web app with six preset slots, a library view for saved stations, and a search interface powered by the Radio Browser API. I built a natural language search feature using an MCP server running on a Cloudflare worker, so users could search for "German jazz stations" instead of wrestling with tags. The app includes achievement tracking (a badge for late-night listening, for example) and curated "starter packs" of stations to help users get started quickly.

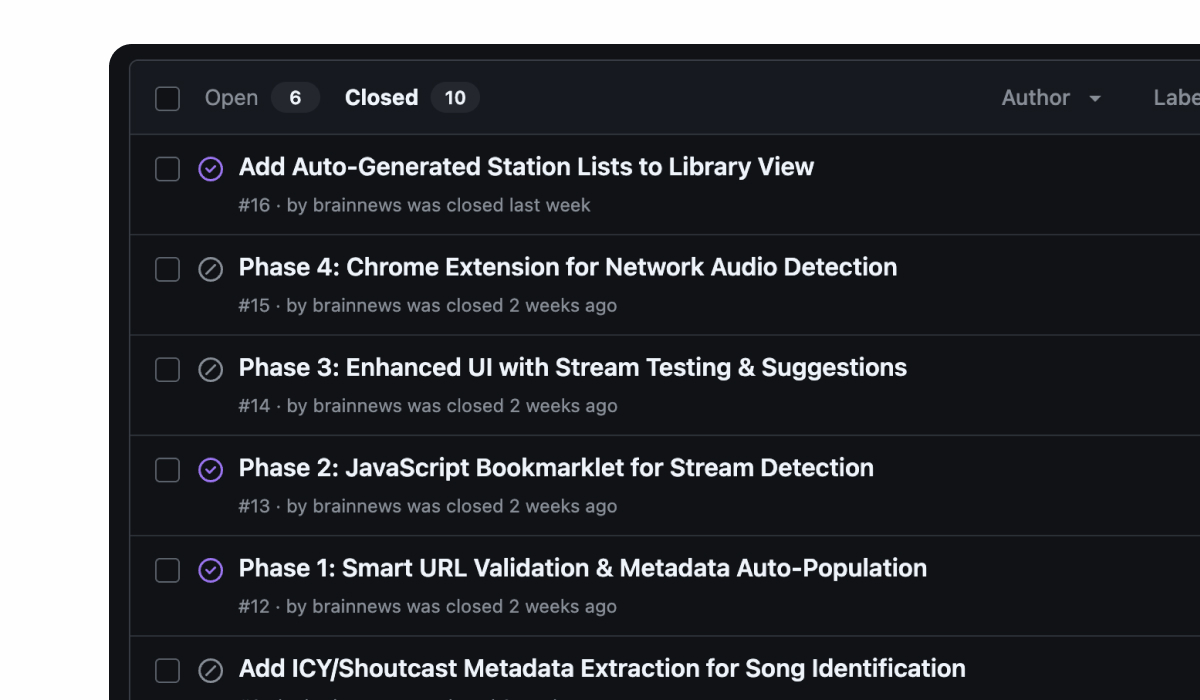

The technical implementation taught me things I'd never bothered learning as a solo hobbyist. But more interesting was the workflow I developed: instead of jumping straight into code, I would describe user stories to Claude Code, which would generate comprehensive GitHub issues with accessibility guidelines, fallback strategies, and implementation phases designed to avoid breaking changes. I could review and edit these issues in natural language, then ask Claude to implement them. This meant my code always worked at every stage – crucial for maintaining momentum, especially for beginners who can get intimidated when things break.

This workflow revealed something unexpected: I'm actually good at the strategic thinking part. When freed from syntax debugging and implementation details, I discovered I excel at articulating vision and making high-level decisions. The division of labor felt natural—I handled creative direction while Claude handled execution.

The experience made me realize that vibecoding has the potential to democratize technical creation in a way that brings back the early internet's DIY spirit. Big tech companies have inflated expectations of what software should be, making creation feel impossibly complex and exclusive. But the fact that McDonald's has made a billion cheeseburgers (and $631.16 billion in the process) doesn't prevent you from grilling one on the weekend for your friends. Just because master bakers create expensive cakes doesn't prevent you from baking one for your child's birthday.

And yet, there are still some barriers to entry. But they’re not where you might expect them. The actual creative problem-solving—describing what you want, iterating on features, thinking through user experience—is remarkably accessible once you get past the setup hurdles. The intimidating parts are the surrounding infrastructure of building software for the public: downloading IDEs, understanding terminals, and managing hosting, DNS, and user privacy. But for many use cases, you don't need that complexity. You can build exactly what you need for yourself, a small internal team, your classroom, or your mom.

I’m using what I’ve learned to plan workshops for my creative team where we'll build radios together, starting with a single hardcoded station and adding complexity gradually. We'll skip the hosting complications and focus on the accessible parts: GitHub workflows, user story thinking, and the satisfaction of making tools for small groups. The goal isn't to create the next billion-dollar startup—it's to reclaim the confidence that comes from understanding how things work.

The world might not end, but your ability to build exactly what you need will serve you well regardless of what comes next. When everything else breaks, you'll be glad you learned to build your own tools, even if you can't remember all the technical details.