The App Spotify Won't Build

The idea was straightforward enough. I stream music constantly on Spotify, but I almost never buy full albums or singles anymore. I figured I wasn't alone in this, and that maybe people would purchase albums if they just knew which ones they actually loved. Spotify, famously and with increasingly annoying fanfare, shows you your most listened albums only once a year. Most citizens of the web know exactly what time of year I'm talking about: Spotify Wrapped. It's become a juggernaut of digital marketing, turning data into a self-portrait to be reflected upon, internalized, and shared with the world. Such controlled data release gives the illusion of transparency and user participation while maintaining a capitalist grip on the stats that keep Spotify profitable for its shareholders. What if there was an app that showed you your most-played albums on Spotify – on demand, any time of year?

I started building BuyMoreMusic on a Friday morning, and I expected to be done by Sunday night. After all, it should have been a simple API request to the user's most-listened-to-albums endpoint. Even with Claude Code handling much of the implementation, this simple project stretched into a weeklong process of trial and error as I hit roadblock after roadblock with Spotify's API. I was right about the code being simple. I was wrong about Spotify's API being open.

The Missing Endpoint

The first surprise came immediately. Spotify Wrapped shows your top songs, top artists, and top albums. But only once a year. Only in December. And only within the carefully choreographed marketing experience of Wrapped itself.

The data exists, but it's released on Spotify's schedule, not yours. And when it does appear, there are no purchase links. Just a button to share your results on social media, turning your listening habits into free advertising for Spotify.

I wanted users to see their top albums at any time of year. I assumed there would be an API endpoint for this, that the data shown in Wrapped would be accessible through the same developer tools Spotify provides for top tracks and artists. There isn't.

There is no top albums endpoint. You can request a user's top tracks and top artists, but albums – the format in which most artists still release their work, the thing with liner notes and sequencing and thematic coherence – simply aren't tracked. Or rather, they're tracked in some internal database, but Spotify has chosen not to expose that data.

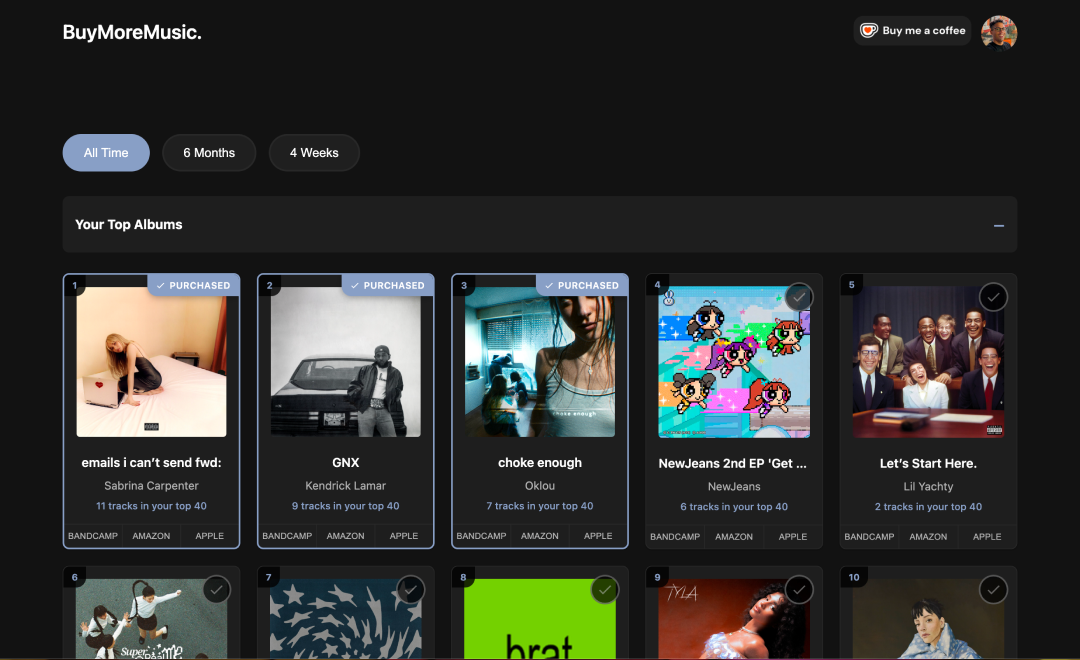

My boy Claude found a tedious but functional workaround: the app fetches a user's top 40 tracks, extracts the album metadata from each, and counts how many times each album appears. If four tracks from the same album show up in someone's top forty, you can reasonably infer they like that album. The app displays this stat for your all-time listens, the past 6 months, or the past 4 weeks.

This missing endpoint isn't a technical oversight. Spotify's interface atomizes music into playlists and algorithmic radio stations. Albums are treated as containers for individual tracks, not as coherent artistic statements. The API reflects this philosophy. If you wanted to build an app that emphasized albums, you'd have to do it despite Spotify, not with their help.

The Twenty-Five User Wall

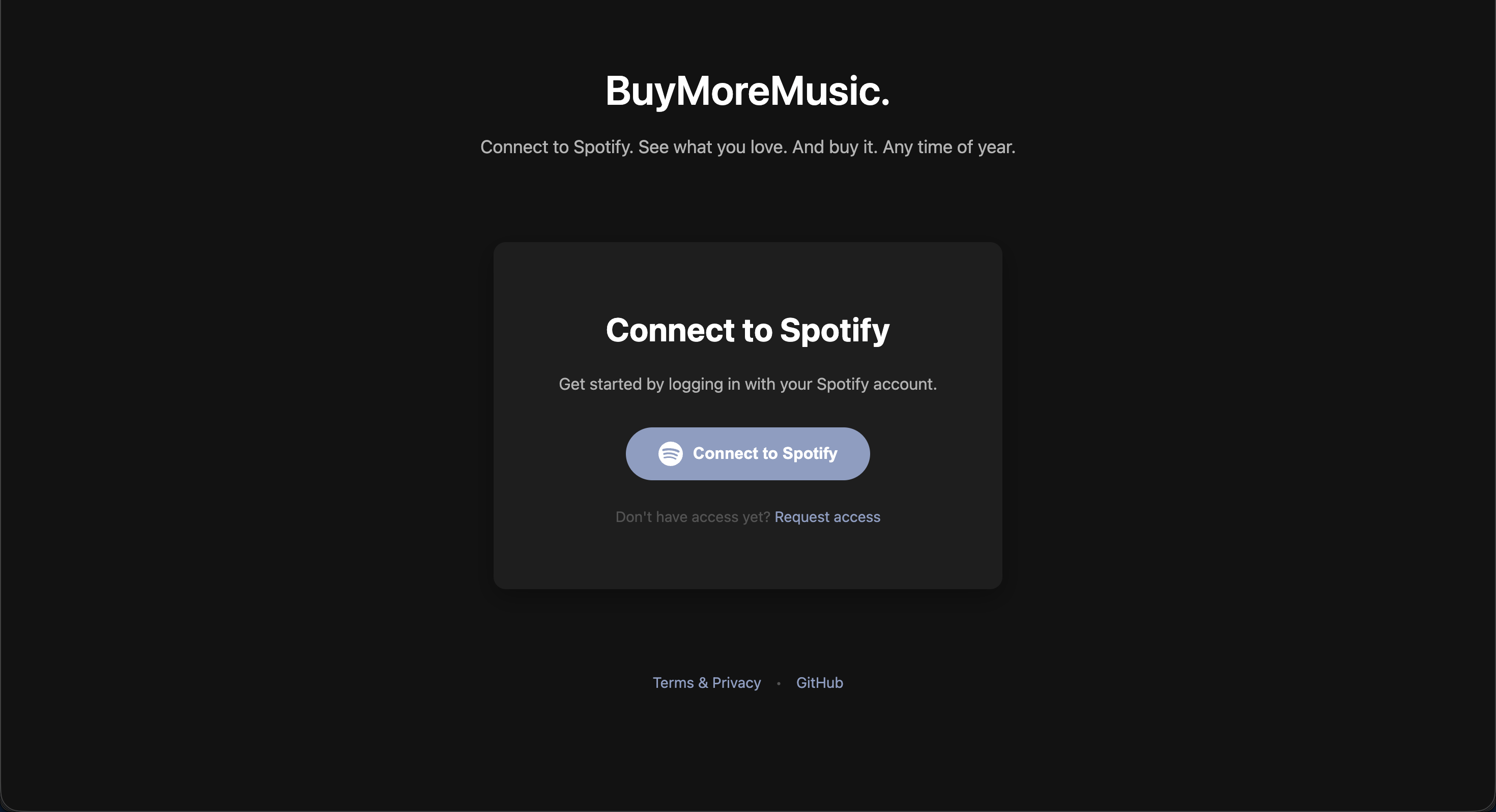

With that simple workaround, the app worked. I gave it a name: BuyMoreMusic. I sent it to my wife and my friend to test. After completing a maddening obstacle course of authentication that feels like the most extreme version of first-world problems and yet could be the thing that breaks a person at the end of a long day, they each received a vague authentication error: "Couldn't connect to Spotify".

I checked the logs, the OAuth flow, the redirect URIs. Everything looked correct. Then I found it – buried in Spotify's developer documentation – a note that development-mode apps are limited to the account that created them.

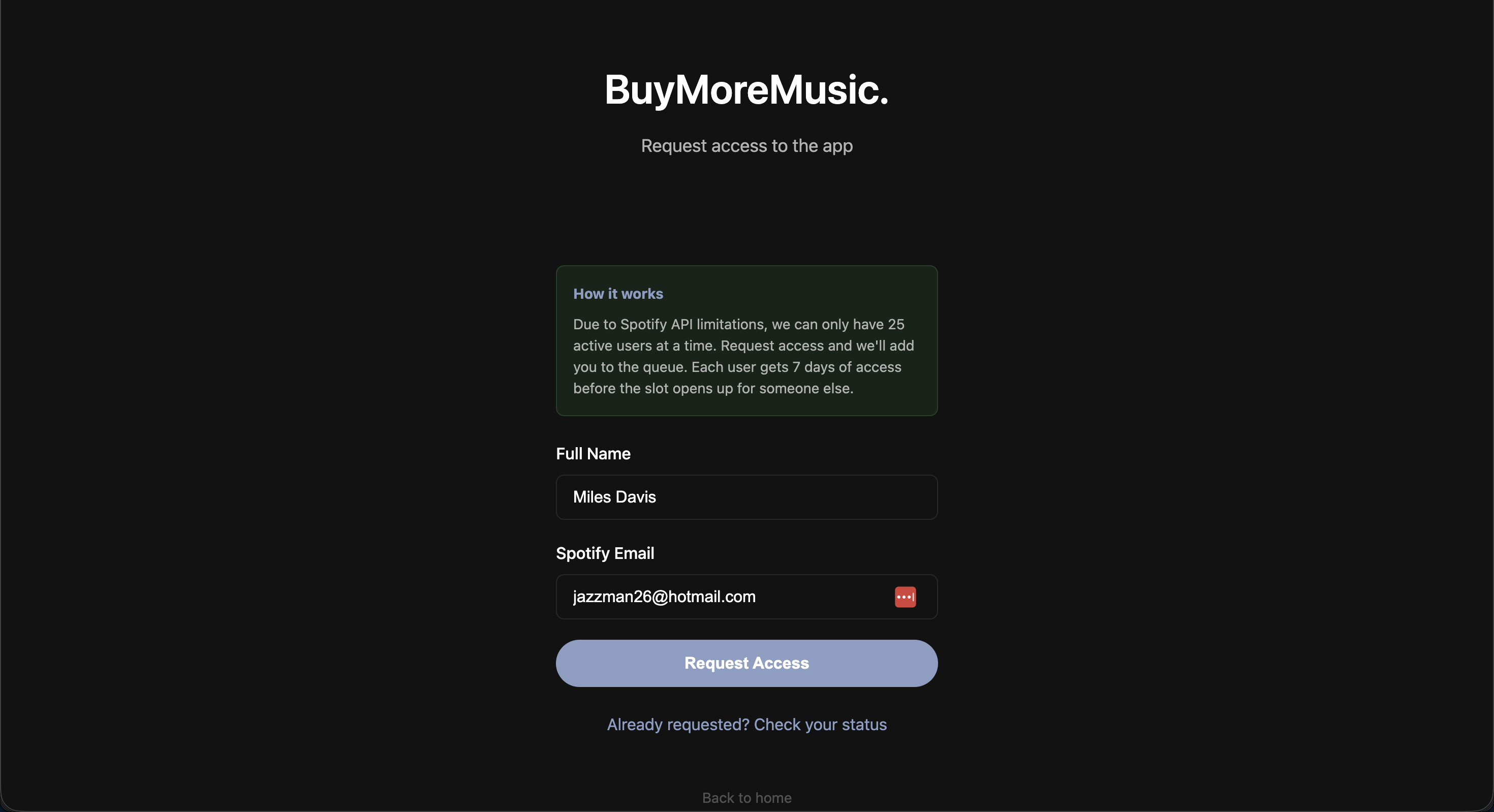

To let anyone else use the app, I had two options. I could apply for "Extended Quota Mode" and undergo a review process that, according to my research, is opaque, slow, and frequently results in rejection. Or I could manually add up to twenty-five users to an allowlist in the Spotify Developer Dashboard, entering their full names and email addresses one by one.

I had built an app that worked perfectly for exactly one person: me. Or, with enough manual work, twenty-five people total.

The obvious solution—the one Spotify presumably wants you to pursue—is to apply for extended access. But I knew what I was building. BuyMoreMusic exists to redirect users away from Spotify and toward platforms where they can actually purchase music. What chances did I have of Spotify approving an app whose explicit purpose was to reduce engagement with their platform? I decided not to wait for permission and, instead, built a workaround.

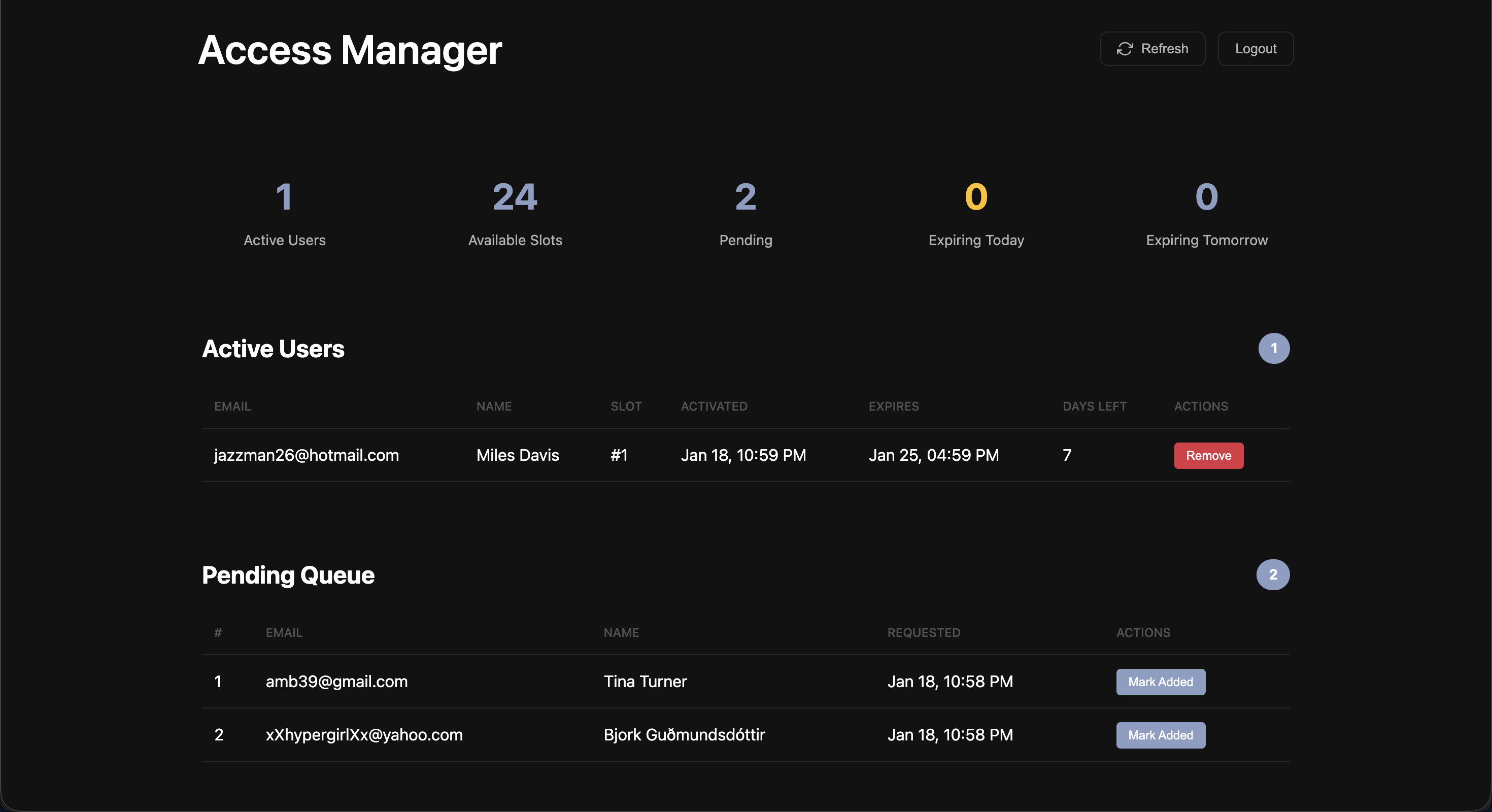

I created a queue-based access management system that allowed users to request access via a web form, wait their turn, and be manually added to the whitelist. Each user got seven days of access before being automatically removed to free up a slot for the next person. I set up a Turso database to track requests, active users, and audit logs. I built an admin dashboard to manage the queue.

It was absurd, yes – an entire user management system just to work around an arbitrary platform limit. But it was also oddly compelling as a model. Think of it like a library with ten copies of a popular book. Not everyone can have it at once, but everyone can have it eventually. The app would never reach the millions of monthly active users that tech companies obsess over, but maybe that's not the only way to measure success.

My attempts at automation included writing a Playwright script with stealth plugins to log in to the Spotify Developer Dashboard and add users programmatically, as well as randomized delays, rotated user agents, and more. Every single attempt was stopped by Spotify's bot detection.

Bummed, but not surprised, I resigned myself to doing it manually.

If this system could be automated – if users could check out access to an app the way they check out books – it might offer an alternative to the growth-at-all-costs mentality that dominates software. Not every tool needs infinite scale. In other words, what if more apps worked for fewer people at a time?

What Spotify Won't Show You

Spotify Wrapped is a masterclass in showing you just enough data to feel personalized while withholding anything that might change your behavior. Once a year, in December, you get your top songs, artists, and albums. You get genre tags and listening minutes. You get shareable graphics designed to look good on Instagram.

You don't get play counts for individual songs. You don't get an archive of your listening history beyond a rolling "Recently Played" list. And crucially, you don't get purchase links alongside your top albums—only prompts to share your listening habits as free marketing for Spotify.

The absence is strategic. Spotify profits from passive listening – from people putting on a playlist and letting the algorithm take over. Intentional engagement, where users seek out specific albums or track their listening patterns, leads to behavior Spotify can't monetize as easily. If you knew your top albums, you might buy them. If you had detailed play counts, you might realize you've listened to the same record two hundred times and decide it's worth owning.

Building Against a Platform

I don't think Spotify is evil. They've made music accessible in ways that seemed impossible twenty years ago. You can listen to nearly anything, instantly, for less than the cost of a single CD per month. That's extraordinary. But accessibility and compensation are different problems, and Spotify solved only one of them.

BuyMoreMusic exists because Spotify chose not to build it. The twenty-five user limit, the missing endpoints, and the long approval process aren't bugs. They're features that protect Spotify's revenue model at the expense of artists and users.

I don't expect Spotify to change. Platforms operate according to their incentives, and Spotify's incentives point firmly toward keeping users streaming rather than buying. But I also don't think we're powerless. Independent developers will keep building these small resistances—tools that route around platform limitations, apps that prioritize creator welfare over engagement metrics.

The real question isn't whether tools like BuyMoreMusic will thrive. They probably won't. The question is why it takes a side project, limited to twenty-five users at a time, to help people support the artists they claim to love. Why isn't there a button next to every album that says, "You've played this sixty times. Want to own it?"

The answer is that Spotify already knows exactly which albums you love, how many times you've played them, and whether you'd buy them if prompted. They've chosen not to tell you.

Try BuyMoreMusic here.